June 18, 2025

The Impact of Trade Liberalization on Informal Labor Markets: Lessons from Mexico

By: Pamela Bombarda, Maria Bas

Tags:

Since the late 1980s, developing countries have become progressively more integrated into the global economy. Despite this advancement, a significant portion of their economic activity remains within the informal sector, predominantly made up of small-sized firms (La Porta and Shleifer 2014, Ulyssea 2018). The reduction in import tariff may improve access to advanced technologies, and thus informal workers can more easily shift into formal sector occupations. This transition is driven by the availability of foreign technology embodied in intermediate goods at lower prices thanks to the trade reforms, which allow formal firms to have higher revenues and increase the demand for labor. We propose to investigate this link using Mexico as a case study. Mexico is particularly relevant due to its significant liberalization process initiated in the late 1980s, and its proximity and economic interconnections with a highly developed economy possessing advanced technology. Our research indicates that Mexican input trade liberalization encourages individuals to transition from informal employment to formal wage work.

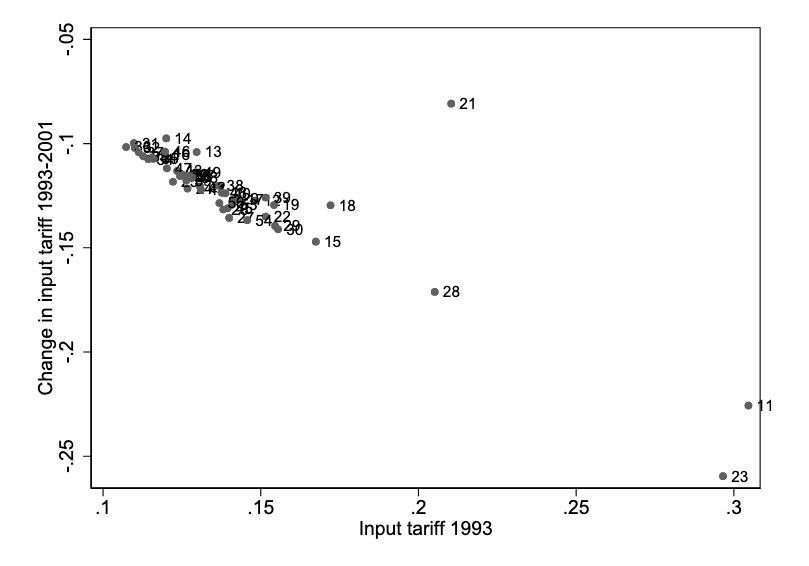

Figure 1: Input Tariff Changes and Pre-NAFTA Tariff Levels (2001-1993)

The Case of Mexico: Institutional Backround

Mexico’s trade policy during the 1970s and 1980s was characterized by a protectionist trade policy with an emphasis on import substitution regime. This strategy aimed to promote domestic industries through high tariffs and extensive import licensing, effectively shielding the economy from foreign competition. In the mid-1990s, however, Mexico began to move toward a more open trade policy. Prior to this shift, the country’s protectionist measures had resulted in limited foreign investment and an isolated domestic market (Szymczak, 1992). The economic challenges of the early 1980s, including falling oil prices and a growing foreign debt crisis, exposed the shortcomings of the import-substitution model and prompted the government to initiate trade liberalization. By 1985, significant reductions in import licensing and tariffs were underway, leading to Mexico’s accession to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986. These reforms opened Mexico’s economy and set the stage for its entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. NAFTA further reduced trade barriers, particularly in Mexico, which had the highest initial tariffs among member countries, and led to a more uniform and reduced tariff structure across industries. Figure 1 illustrates this input tariff convergence, indicating that industries with the highest initial tariffs experienced the most significant reductions over the period.

Effect on Labor Reallocation from Informal to Formal

The theoretical channels through which input-trade liberalization affects the reallocation of labor from informal to the formal sector can be rationalized as follows. Formal firms face fixed labor regulation costs and variable costs (taxes) but gain access to high-technology, more efficient foreign inputs. Informal firms avoid these costs but face a probability of detection. Firms decide whether to operate in the formal or informal sector based on their profitability. If foreign inputs are complementary with skilled labor, input tariff cuts lead to more pronounced reallocative effects from informal to form sector for skilled workers. Under these assumptions, input-tariff reductions lower the relative unit costs of formal firms, increasing the probability of becoming formal and thereby the demand for formal employment.

In recent work (Bas and Bombarda, 2024) test the relationship between input-trade liberalization and the reallocation of workers from informal to formal firms. We combine household-level data from Mexico’s National Urban Employment Survey (ENEU) with information on tariffs applied by Mexico to U.S. products and U.S. tariffs on Mexican exports during 1993–2001. ENEU provides data on wage workers, defined as individuals reporting a fixed wage, salary, or daily wage, as well as their access to health insurance and social security coverage, which we use to classify workers as formal or informal. Following the methodology of Goldberg et al. (2010), we compute Mexican input tariffs applied to U.S. goods, restricting our sample to manufacturing sector workers due to data availability.

Our identification strategy exploits variation in input tariffs across industries over time. Mexico’s high initial tariffs and significant reductions under NAFTA provide a natural experiment. Between 1993 and 2001, input tariffs on intermediate goods from the U.S. fell by more than 12 percentage points on average, from over 14% to less than 1.7%, while Mexico’s imports of inputs from the U.S. increased sevenfold. To address potential endogeneity concerns, we provide evidence that input-tariff changes were not correlated with initial industry characteristics and show that pre-NAFTA tariff reductions during the 1980s did not affect informal-to-formal transitions prior to NAFTA.

Key Findings

The findings in Bas and Bombarda (2024) shed new insights on the effects of input-trade liberalization on informal labor markets. Workers in industries that experienced the largest input-tariff reductions were significantly more likely to transition to formal employment. Specifically, workers in industries with average input-tariff reductions of 12 percentage points saw a 3.5-percentage-point increase in the probability of formal employment compared to observationally similar workers in industries with smaller tariff reductions.

This effect is particularly pronounced for high-skilled workers (those with more than 14 years of education), who experienced a 4.6-percentage-point increase in the probability of formal employment. These findings confirm that the complementarity between foreign inputs and skilled labor is a key channel driving the reallocation of workers from informal to formal jobs. Importantly, our results remain robust after accounting for alternative mechanisms, such as foreign competition (captured by output tariffs) and market access (captured by U.S. tariffs on Mexican exports).

Several robustness checks are carried out to validate these findings. First, we examine the role of maquiladoras, given their prominence in Northern Mexico as export processing zones. Our results show that maquiladoras do not significantly influence the allocation of workers between informal and formal employment. Second, we use an alternative measure of input tariffs based on more disaggregated input weights from 1992 U.S. Input-Output tables. Third, we perform a falsification test by analyzing transitions from informal employment to unemployment, finding no evidence of a similar pattern. Finally, we assess whether input-trade liberalization has differential effects on formal employment shares across municipalities, confirming that our results are robust and consistent across all sensitivity tests.

Final Remarks

Bas and Bombarda (2024)’s study highlights the significant impact of input-trade liberalization on informal labor markets in developing countries, with a particular focus on Mexico. By reducing input tariffs, NAFTA facilitated the adoption of foreign technology and increased demand for skilled labor, driving a reallocation of workers from informal to formal employment. There are compelling reasons to believe that this reallocation has been advantageous for workers. Employees in the formal sector typically enjoy better working condition, associated to the nature of the formal job, more stable, with higher wage, protected by labor laws, and associated to social security benefits. These findings underscore the importance of considering the informal sector when evaluating the broader labor market effects of trade reforms, particularly in developing economies where informal employment is a substantial part of the workforce.

References

Bas, M, and Bombarda, P. (2024). « Foreign Technology and Informal Employment: Evidence from Mexico,” THEMA working paper 2023-2.

La Porta, R. and Shleifer, A. (2014). “Informality and development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3):109–26.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). “The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity,” Econometrica, 71, 1695–1725.

Szymczak, P. (1992). “International Trade and Investment Liberalization: Mexico’s Experience and Prospects,” chapter 04. International Monetary Fund, USA.

Ulyssea, G. (2018). “Firms, informality, and development: Theory and evidence from Brazil.” American Economic Review, 108(8):2015–47.